Thanks to Sci-hub, its predecessors and open journals, I have had the opportunity to read far more than just the abstracts in thousands of medical studies in my life, if not tens of thousands. A fair share of them were about nutrition and other personal interests, such as being able to recognize the shortcomings of science and the current zeitgeist. Although I am just a layman, the extreme amount of studies I have read in detail far surpasses that of most practitioners, and puts me into a rather strange position.

If you want to understand nutritional science, you have to understand a bit about how medical science works. In medical science you have something called placebo controlled randomized double-blinded trials and prospective cohort studies, without which the greater whole of medical science would essentially be discredited and an unreliable nightmare, where no one really knew what was true or false to begin with. Unfortunately such trials don't exist in any form or shape in nutritional science and cohort studies are also very different. For double-blinded studies, you would have to force-feed people all the food they consume for decades with feeding tubes. And if you had placebo groups, the people in it would just starve to death. In prospective cohort studies on the other hand, people are rarely if ever force-fed strict diet plans the same way as if taking a certain type of drug, and this kind of study is much less commonly done than it is in medicine. So there are clearly huge issues with how studies are conducted, and due to the complexity of food compared to just single substances and pills, the conclusions we derive from them are not the same as we can derive from scientific studies in other fields.

Ok then if we so to speak can't really have reliable or robust scientific studies, we do still understand something about metabolic function and nutrients to be able to make conclusions? Yes this is true, but what we understand is very limited as well. Vegan studies and fasting studies for example have shown, that even if people consume wildly insufficient amounts of vitamins and other micro nutrients, at least most people's bodies get very very efficient at budgeting whatever little is left and still made available almost indefinitely, such that no hard physical signs of malnutrition will manifest. What other effects this budgeting has on mind and body, we don't really know. We also do not understand the gut microbiome much at all, which is at the heart of good health and nutrition. We do not understand what individual differences in people exist, that make semi-essiential amino-acids more essential in one group of people but less in the other. We do not really understand how an abundance or relative shortage of substances such as DPA, EPA, tyronsine, Q10, creatine, carnosine, B vitamins, choline, carnitine and so forth influence health on the long run, and how much people are individually constituted to metabolize them from one food source or the other. In summary, what we understand on a cellular and metabolic level is so limited that you hardly can draw any if any at all concrete nutritional advice from it, and individual differences between people due to genetics or old age can be enormous. Often even worse, due to scientific reductionism (aka scientism), whenever people attempt to argue on this basis, the conclusions can be misleading and wrong (e.g. about dietary cholesterol being harmful, or fructose as a better sugar alternative), as they do not factor in the whole picture that you can factor in if the scientific understanding wasn't as fragmentary and incomplete as it was or is at the time.

But then how do observational nutritional studies work at all? Often people are essentially given questionaires about what they ate the last 20 years, and then studies make seemingly outlandish findings, such as that eating more than 2 eggs a week is associated with adverse health outcomes just as much as smoking cigarettes. Or that eating white meat is associated with better health than red meat. Or less meat with better health. It is not that those studies are wrong, too small, or have methological problems. It is just that we cannot draw any actually useful conclusions from them. People who do this, or suggest that this is possible, commit to various non sequiturs, such as the converse error and that correlation does not imply causation. In actuality, people might simply crave to eat eggs if there is something wrong with their cardiovascular system, because they crave cholesterol which the body needs to patch damaged endothelium inside the blood vessels. Also people might recall what they ate wildly incorrectly, and they may not adhere to strict diets much at all, despite stating so, especially if they are very strict and very complicated. Or the methodology has issues, such as categorizing or not categorizing fast-foods and food preparations as "eggs", simply because they contain eggs as a minute ingredient. This is indeed one of the main drivers how we have meat studies that associate meat with adverse health outcomes: meat is everywhere, especially highly processed foods and "meat" such as burgers or sausages. But this is by no means the same "meat" you would eat inside a healthy diet scheme. People who choose chicken wings (white meat) and salad at Burger King, instead of the big Double Whopper with cheese (red meat) and icecream, are the people who end up driving those kinds of statistics. Someone who is health-conscious however, eats lots of vegetables and naturally avoids take-away fast-foods, because of whatever dietary constraints, will often be the one who is counted as someone who has "reduced meat" in their diet. On the other hand, people who don't think about what they eat, aka eating "the standard diet", will be counted as "meat eating" or "not meat reduced" in studies. And people who eat more meat when trying to be more health-conscious, do hardly exist at all.

But what exactly is "the standard diet" in research? If you were to go to a supermarket and grab one piece from every shelf, this is more or less the standard diet: A pack of flour, a pack of sugar, a pack of bread, a banana and an apple, a yoghurt with sugar, a pack of cheese, milk or milk with cacao and sugar, sausages, a jar of pickles, a can of beans, a pack of noodles, a pack of rice, a sack of potatos, a bottle of wine, a sixpack of beer, a bottle of gin, a pack of bonbons, various pieces of chocolate and candy, two packs of chips, prezels, a six pack of mountain dew, a pack of pizzas, chicken wings and lasagna. Plus everything you can buy at fast-food chains such as McDonalds or Pizza Hut. In short: The standard diet is to simply mindlessly consume whatever you feel like and what sells cheap, because you just don't care and think about what you eat. Regardless if it makes sense or not, this is "the standard diet" (also called "meat-inclusive" or "meat diet" in vegetarian studies) and the actual scientific baseline to compare anything in nutritional science to. Obviously it isn't hard at all to find a diet style that shows some kind of measurable improvement to it (such as reduction in obesity or cardiovascular issues). Even if this diet style would fair worse than following some other healthy diet plan, which it will be never compared to.

But this also escapes common sense: We don't need science to tell us that eating crap like a mindless idiot somehow is unhealthier than thinking about what you eat. Or that processed foods and fast foods are unhealthy. But this is sadly what a lot of people are trying to sell when advocating nutritional science by overstating or oversuggesting what research findings can really tell us. At least insofar as that we don't suffer from certain severe medical conditions to begin with, which do warrant greater concern and might be subject to greater medical insights.

Also many other issues need to be factored in when analyzing studies. For example the government might be very keen on funding lots of studies on how people can live healthier lives while eating a diet of corn syrup and insects, algae and other cheap dirt - so they have more farm land to support their biodiesel and bioethanol scam. But no one ever funds any studies on how to live healthier on a diet that is mostly made up of wild grass fed water buffalo, phesants, whale liver oil, truffels, Nakazawa cows' milk and Manuka honey - which might or might not be wildly superior somehow. In fact little research has been done even just about ketogenic diets (i.e. diets that mostly rely on meat, and fat for energy), although it has been scientifically known and suggested as an option for decades to address a wide range of problems, such as obesity, mental health issues and diabetes. Funding bias and lack of research due to selective funding is one of the single most biggest problems in science we face today.

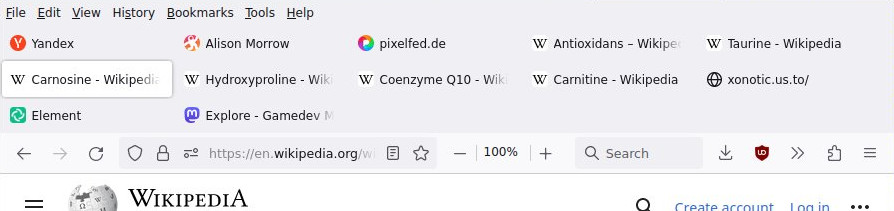

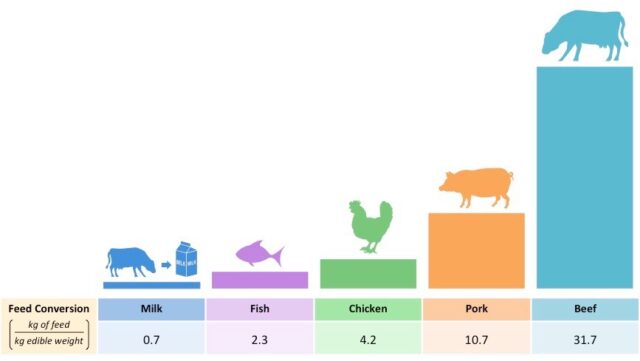

Red meat (pork & beef) requires over 6 times more feed and much longer timeframes to produce the same amount of meat as white meat (poultry, fish). It also produces about as much more emissions plus other costs. This has put the industry and government on a hunt in tandem, to manufacture data that associates red meat with adverse health effects. Conversely no one funds studies to the contrary. Red meat studies that do not include processed meats equally do not exist.

But not only science is affected by heavy bias. Considerable lobbying efforts exist on the internet that distort nutritional information, such as the vegan and vegetarian lobby, who create a large portion of nutritional blogs and Youtube videos. This is not only because of advocacy, but in part also because it is just so complicated to follow their diet scheme, and the amount of information put forward is just orders of magnitudes higher than in any sane diet style. One that you can entirely explain on essentially just one page, or with just a few uncomfortable bullet points, that no one really wants to hear. Vegans and vegetarians however do not eat food for health reasons, but for ideological reasons, i.e. for animal wellfare or to save the climate. This alone should make you question if their advice can be taken serious at all. And the same problem leeches into research as well, as prescribing veganism and environmentalism is somewhat of a bigger fad amongst highly educated people. To the contrary though, studies have found that the majority of vegans suffer from malnutrition in western countries such as Germany, UK or US. Yet this research is buried and denied so much that it will strike most people with total disbelief, and of course the people affected somehow manage to remain totally oblivious of the fact. It might be that one out of a felt one hundred people is genetically constituted to naturally cope with vegan nutrition. And this is the guy you see on Youtube advertizing it. But for the rest of us, essentially anyone who has ever seriously tried, it will not replicate this experience and be a total nightmare, which studies reflect and acknowledge to some major degree, with very high drop-out rates and people showing concerning blood markers.

The amount of distortion you have to face in science even with placebo controls and rigorous prospective studies is staggering. But if you don't even have that, it is all just a huge confounded mess.

The only diet plan that is somewhat scientifically well-supported in its positive health effects is the "mediterranean diet". This is not actually a diet that people eat in the mediterranean region, but it developed from a fantasy that scientists had about it in the 60s (olive oil, red wine and fruits) and it just was spun further and further within scientific circles over time to support research findings. Now it denotes an entirely different style of diet, that doesn't really have much of anything to do with mediterranean cousine. Even if the research about its health effects seems solid, it is still very important to consider, that this research was initially and mainly done with sick people in mind. This automatically means, that it includes or targets mainly old people, since the older you are the more chronic health diagnoses you get. Old people also make up a major part of the population nowadays. It might make perfect sense that the average 67 year old with diabetes, arthritis and high blood pressure, is much more likely to become incompetent to digest normal healthy meals, because of impaired organ function. Thus of course in those kinds of people it will show substantial health benefits to e.g. reduce the amount of protein in the diet or even cholesterol, and this truly makes sense for them. However if the same is done to healthy subjects, at least in animal studies, often the reverse turns out to be true. This is why we simply don't know if it truly makes sense for normal healthy people to reduce the amount of meat in their diet. But likely at a certain low threshold of reduction, normal people can just easily cope with it while old and sick people would certainly not, without dietary intervention. Hence studies show significant benefits from reducing red meat by some 30% over average. The government obviously just loves it as well, and it is put forward everywhere as a one size fits all advice. But if you are not old and frail to begin with, you might just be the one trying to save at the wrong end and don't do yourself any favors. Especially so the younger you are.

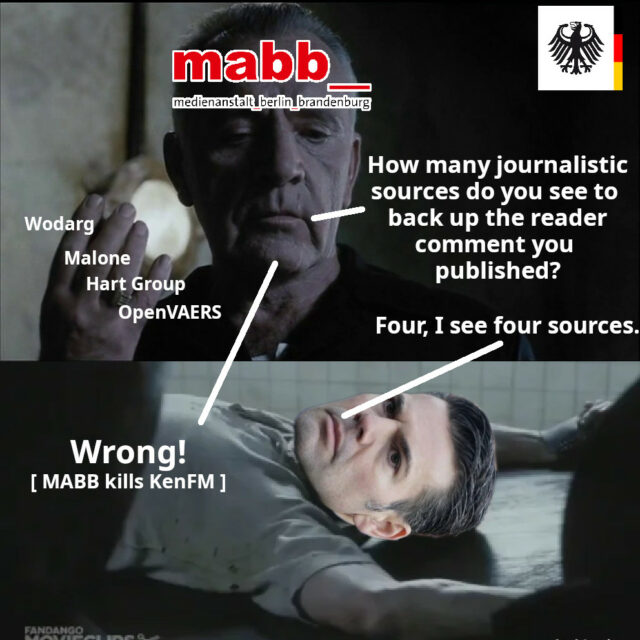

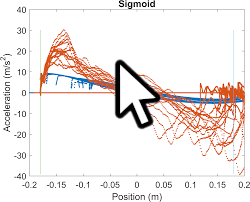

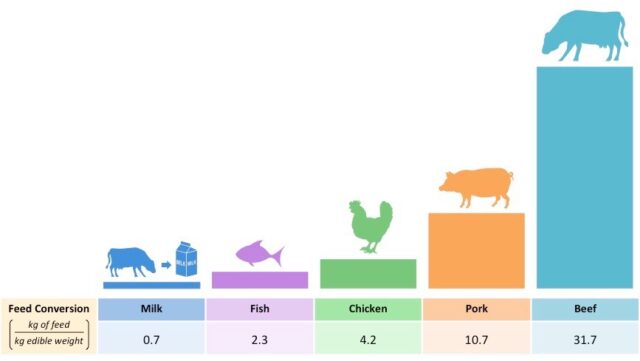

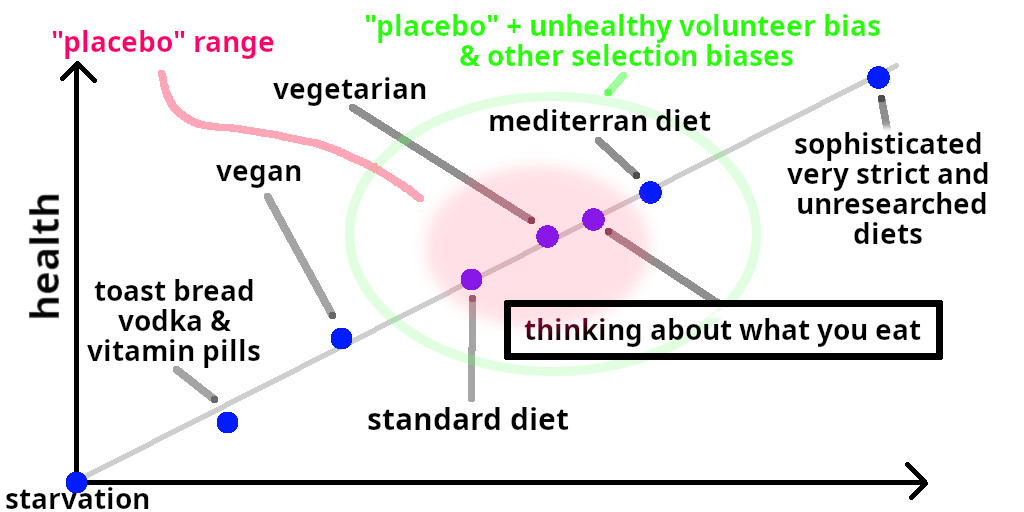

To summarize all this, I have drawn this cartoon on how you can think of the capabilities of nutritional science to draw conclusions about certain diet styles. I am not exaggerating in that most of the why and hows in research findings still remain a mystery. And everything you hear in blogs and official health advice must be questioned and taken with a grain of salt. Most diets will lead to improvements, simply because anything is better than not thinking about what you eat. Even if it makes no sense at all, such as eating only red foods on Monday and only green foods on Tuesday, yellow foods on Wednesday and so forth (hence excluding a lot of fast-foods most days). In the end what is best or not cannot simply be bought by listening to opinion pieces, or following government advice. But only with critical thought, common sense and by reasoning about it outside of the current paradigms.

What is important to recognize however is that strict and sophisticated diets, such as my diet style, are simply not researched. We only know from anecdotes, be that scientifically with "ketogenic" diets or sites like meatheals.com, that people not only experience health benefits but often even impossible improvements, such as curing type 1 diabetes, IBS or ADHD, by eating essentially just meat and nothing else. People don't seem to report such extreme improvements on such a comparably large scale for a fringe minority, with any other food or diet style. So it shows what potential this one single food has.

Also meat and animal products contain many substances that people have never even heard of, and that do not occur much or at all in plant sources, but which exert surprising health benefits if consumed in excess quantities. Some of which do remarkably increase physical fitness, athletic or mental performance or longevity. For example: choline, 4-hydroxy-proline, DHA, DPA, EPA, carnitine, creatine, vitamin K2, vitamin D, calcium, B12, and even extremely potent anti-oxidants such as carnosine, anserine, coenzyme Q10 and taurine or cofactors to antioxidants such as selenium, zinc, or vitamin E. Research about those endogenous substances is often very sparse and new, while research of exogenous anti-oxidants is "somehow" extremely abundant and overwhelming. So there is not telling how many substances and their astonishing health functions are yet to be discovered.

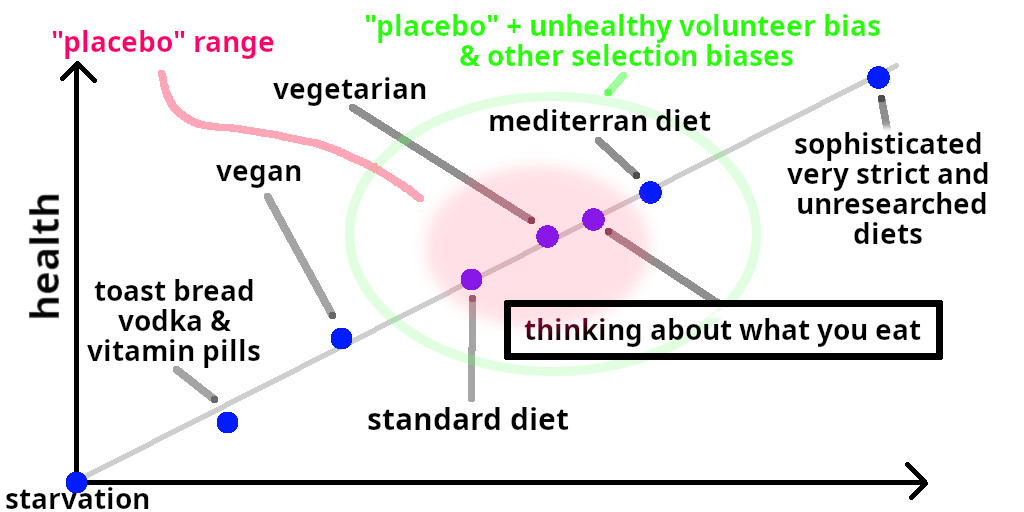

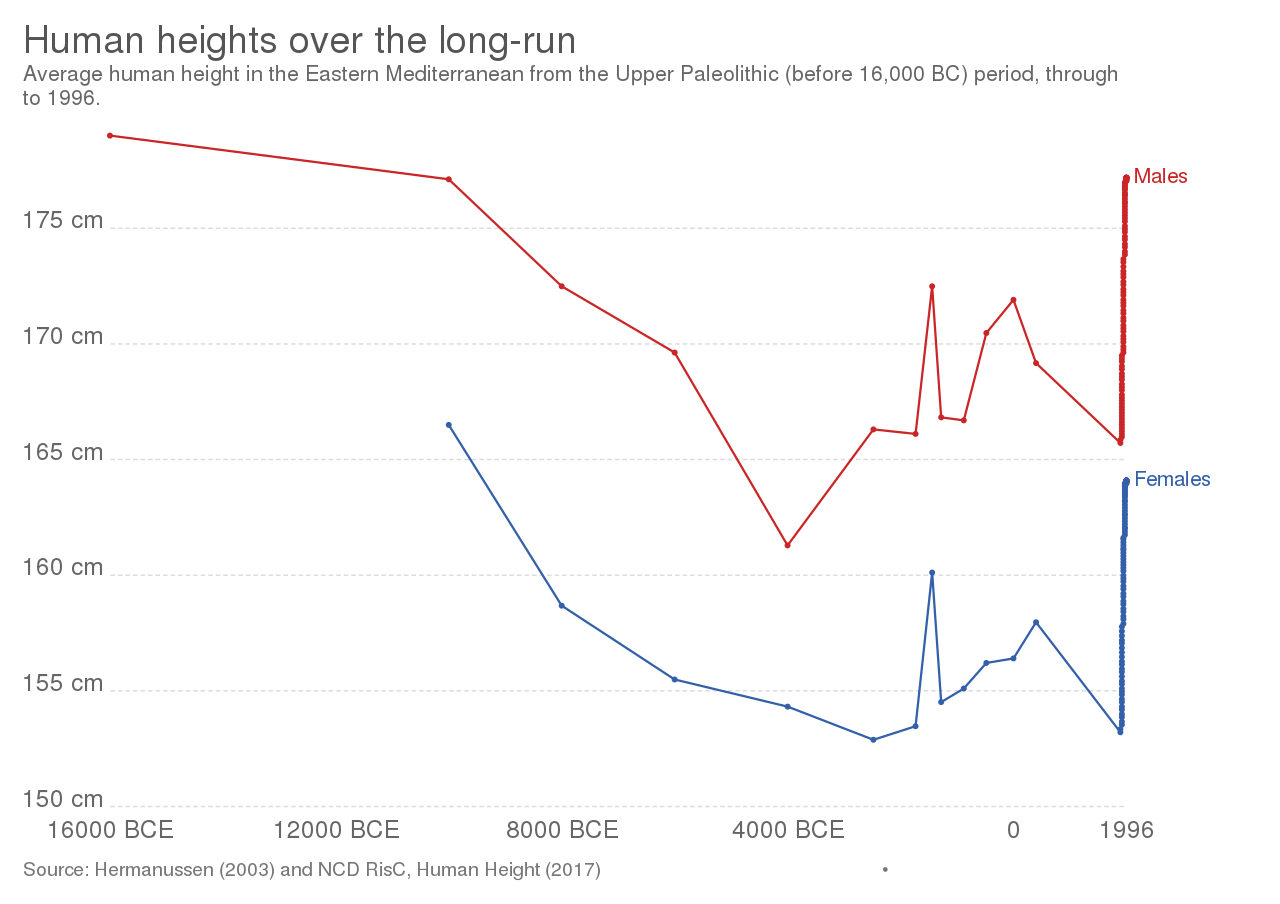

With the advent of agriculture and the adoption of an unnatural deficient nutritional style, average body height has decreased dramatically, and has still not fully recovered to the heights of mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies, despite recent abundances of food and increases in meat consumption.

With the advent of agriculture and the adoption of an unnatural deficient nutritional style, average body height has decreased dramatically, and has still not fully recovered to the heights of mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies, despite recent abundances of food and increases in meat consumption.

For certain it can be said, that meat is much much closer to what our body needs, simply because our bodies are mostly just made up of it. It might be possible for our bodies to go the extra mile to convert plant material to meat material, because of extreme evolutionary adaptation. However there is a certain logic to it, that cutting out the middle route might come more natural and easy to our metabolic systems. With less challenges involved, such as metabolic conversions, fighting anti-nutrients, endocrine disruptors and other latent plant poisons that were developed over time against us. Those things might not work properly anymore in people with poor gut health, or who are just genetically constituted differently. Or they never worked that well to begin with, because the biochemistry and microbiology for it just has to be too complicated to yield great results. Those are all big unknowns when considering whether it is better or worse to reduce or increase meat in your diet.

While I don't think that eating just meat and nothing else is really a good diet style, the new "carnivore" internet phenomenon, with some scientific background, challenges everything we thought of as substantiated before in nutritional science, and what we believe to be healthy. First it illustrates that meat contains virtually all the micro nutrients that the body needs (although it is obviously lacking here and there especially on certain electrolytes), while plants only really contain single nutrients, such as lemons containing just vitamin C, with certain seeds being somewhat of an exception to that, which most people don't commonly know of. But it also shows at numerous examples, such as vitamin C requirements being reduced by orders of magnitude when not eating any sugars, that it is the particular combination of foods that matter. And that we can likely attribute this to simply evolutionary adaptation. I.e. that our ancestors were forced to survive on meat and nothing else for months at a time during winter. Most of what we understand scientifically often only holds true to the "standard diet", which consists mostly of wheat products, refined sugar, and to some extent also meat and alcohol. On the other hand, conflicting information such as from the carnivore diet or different diet schemes, is simply by far and large ignored in nutritional science. If I were to drink a beer or two in the evening, like a lot of people after a meal with a lot of meat, I would certainly get gout and kidney stones. And this reflects in scientific studies as meat being associated with gout. Although we know now that meat alone does not cause gout. But how does that make sense for me personally to draw smart conclusions from for my own life? Should I cut out the meat, or should I cut out the beer and potatos?

If you live very health conscious, and are not careless in what you eat, then you will find that nutritional advice is often very limited, single-minded, simplified and misleading. We actually don't understand a whole lot about the body, gut and metabolism. What is good or bad is still best addressed by common-sense decisions, and just personal experience and trial and error. Don't eat just what tastes good, but what makes you feel heathier. Experiment what works best on your own body. Try one radical style, such as veganism, and then try another radical style, such as carnivore and find the in-between that is best. See what difference it makes. Reason and guess why it makes sense to eat some foods and not others. For example evolutionary speaking, wheat is still quite a new thing for the human race, and there are countless minorities who still have issues with it, because they lack the genetic adaptation. Some things like alcohol and refined sugar are just bad. On the other hand people have survived for hundreds of thousands of years on mostly just meat in winter times. Eggs and fruits were only available during certain times of the year and in limited quantities. This reflects in the science. We now find that too much fructose consumed all-year around will lead to detrimental liver changes. And maybe you really should not eat an egg a day. But 30 years back, science was advocating fructose as a healthier sugar. We could have seen this coming, with simply common sense, and thinking about what our ancestors ate.

When science is limited, appealing to scientism makes you blind and is more often than not ill-advised and misleading. Nutrition can certainly benefit from scientific insights, however it would be very premature to root it in science entirely. Especially so if the people advocating scientific findings, do themselves not understand them properly, or have ulterior motives that do not have your best possible health status in mind. This could affect your mental performance, emotional or physical wellbeing all alike.

Some people do really fine by just eating fast-food. Most people just think they do. For others it has more serious consequences, and even crippling disease. It is important to experiment and find a diet style that is healthy and works best individually.

At the end, another little story about a mushroom called paxillus involutus. It was eaten for hundreds of years, and not recognized as poisonous. Most people didn't experience any issues from it at all. If you had conducted studies on it, it would have shown that it is a healthy food for most people, and only small minorities would show sensitivity reactions, similar to how only very few people experience full-blown Celiac disease (gluten sensitivity) or Chron's disease when eating wheat. So this is a healthy food right, if most people are fine, there is no reason for concern? Wrong. We now know that this mushroom gets more poisonous over time, sometimes many years, because it stimulates autoimmune reactions and it can eventually lead to organ failure. But it took hundreds of years of science to advance to the point of being able to recognize this. From just people's observations, the mushroom was really fine to eat. You could have asked 10 people if this mushroom was good, and 10 would have said yes. This is not to say that wheat can be deadly, but similarly it has been associated with immunological processes that can have detrimental effects on health to various degrees that only really develop over long timeframes. Food is just a very complex thing in nature. As there are hundred of thousands of chemicals in food, hundreds of foods, hundreds of microbes, proteins and enzymes involved in digestion, it stands to reason if there aren't just as many points of failure. Small minorities go entirely unnoticed in scientific studies and natural observations. With food we might face a situation where most things work out for most people and some things just don't work out for most people, we just don't know what the latter are, because it is so individual. It is up to you to conduct some science on your own, to see what works out for yourself.

With the advent of agriculture and the adoption of an unnatural deficient nutritional style, average body height has decreased dramatically, and has still not fully recovered to the heights of mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies, despite recent abundances of food and increases in meat consumption.

With the advent of agriculture and the adoption of an unnatural deficient nutritional style, average body height has decreased dramatically, and has still not fully recovered to the heights of mesolithic hunter-gatherer societies, despite recent abundances of food and increases in meat consumption.